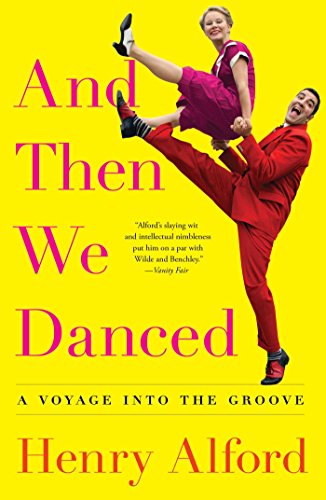

Items related to And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

When Henry Alford wrote about his experience with a Zumba class for The New York Times, little did he realize that it was the start of something much bigger. Dance would grow and take on many roles for Henry: exercise, confidence builder, an excuse to travel, a source of ongoing wonder and—when he dances with Alzheimer's patients—even a kind of community service.

Tackling a wide range of forms (including ballet, hip-hop, jazz, ballroom, tap, contact improvisation, Zumba, swing), this grand tour takes us through the works and careers of luminaries ranging from Bob Fosse to George Balanchine, Twyla Tharp to Arthur Murray. Rich in insight and humor, Alford mines both personal experience and fascinating cultural history to offer a witty and ultimately moving portrait of how dance can express all things human.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

THE INSTRUCTOR, AN ATTRACTIVE, WELL-DRESSED woman of a certain age named Jean Carden, looks out at a group of forty boys and girls aged nine to fourteen. We’re at the Gathering Place, a large, antiques-dappled catering hall in a sleepy town in North Carolina called Roxboro (pop. 8,632), and the kids are all dolled up: the boys are in blue blazers, neckties, and khakis, and the girls are in party dresses and white gloves. The young folks’ collective mood is a study in agitated boredom—imagine a DMV for people who still drink juice out of boxes.

In her honeyed Southern drawl, Carden asks the group, “Do you all recall how to sit pretty? Who’s going to sit pretty for me?”

An intrepid eleven-year-old boy raises his hand, and then, given the go-ahead by Carden, awkwardly motions to his partner to take her seat. As the boy lowers himself into the chair beside hers, he remembers to unbutton the top button of his jacket, as instructed.

Carden commends him warmly and then asks the group, “Now, who would like to demonstrate escort position?”

* * *

This is a cotillion, as offered by the National League of Junior Cotillions, an organization established in 1989 with the purpose of teaching young folk how “to act and learn to treat others with honor, dignity and respect for better relationships with family, friends and associates and to learn and practice ballroom dance.” There are now some three hundred cotillion chapters in over thirty states.

Of all the functions of dance that I’ll write about, Social Entrée (along with the possible inclusion of Religion) would seem at first blush to be the most rarefied. But that’s because, when people think of dance as a vehicle for social advancement, their brains alight first on fancy balls, an admittedly infrequent event in any mortal’s life. But once you factor in the cool points or prestige to be earned from going to nightclubs or certain other dances, or to any kind of concert dance, especially ballet, the map for advancement gets decidedly bigger.

The Social Entrée function is usually a form of connoisseurship. Typically, man’s dignity is linked to thought—the less practical the thought, the more esteem we give it—but who says that ornamental movement and gesture can’t occasionally yield respect, too? Moreover, as with poetry and opera, dance and its mysteries, not to mention its occasional extravagances, can elicit rolled eyeballs from the stoics and the uninitiated in the crowd—which, in a reverse-psychological way, can strengthen the resolve or exaltation of any individual hip enough to “get it.” Membership may, as the advertising world tells us, have its privileges; but rarefied membership has privileges and a vague sense of superiority or resolve.

The session of cotillion I’m watching is number two; after a third class, in a month’s time, the kids will attend a ball at a country club in Durham, some forty minutes away. During the ninety-minute class, Carden intersperses the five dances that she teaches—these include the waltz, the electric slide, and the shag—with manners drills. The drill that reoccurs the most—four times—is introducing yourself to others in the room. Carden repeatedly sings the praises of eye contact and a strong speaking voice.

Sometimes the vibe of Bygone Era in the room gives way to heavy irony, usually as prompted by the music played for each assigned activity. When doing a box-step waltz, for instance, many of the kids’ affect of grim penitence stands in dramatic contrast to a musical accompaniment the lyrics of which urge them twelve times to “let it go.” At another point Carden tells the kids to stand at one end of the room and then to approach her one at a time and introduce themselves. But when she cues the music, the hall fills not with the slinky samba or light processional music that you’d expect, but rather with a heartrending and poundingly operatic version of “Ave Maria.” It’s a synod with the Pope.

Toward the end of the session, Carden tells the boys to escort the girls to the refreshment table and to avail themselves of lemonade and cookies. Seldom do you see a level of concentration like the one displayed by a nine-year-old boy, under the watchful eyes of a chaperone, a dance instructor, and thirty-nine hungry colleagues, using delicate silver tongs to wrangle a large, floppy, soft-baked cookie. It feels like brain surgery for an audience of cannibals.

Then, once the kids are all seated and nibbling, Carden tells them about their homework. They are to practice rising from a chair five times; to introduce themselves to a new acquaintance; to introduce someone younger to someone older, and someone with an honorific to someone without one; and to give two compliments to family members and two to friends.

When the class is over, I chat up a group of kids, including a shy, ten-year-old boy who spends a lot of our conversation staring at the floor. I ask him if he had fun during the last ninety minutes of his life, and he robotically answers yes. Then I ask him if he thinks having taken cotillion classes for a year has helped him at all. He stares at the maple floorboards beneath us and says, “I like to know what to do when maybe I’m in a restaurant and there are five hundred forks.”

* * *

I hear ya, kid. My mother sent me to ballroom dancing classes when I was in the fifth grade. “It’s what you did then,” she told me recently, referencing the way a generalized feeling imparted by the media and acquaintances you meet in the produce section of your grocery store starts to simmer and simmer, finally bubbling over into an act of indeterminate purpose and questionable worth.

Previously, my mother had sent my three siblings to ballroom classes, too. When I asked my brother, Fred, what he thought had prompted her, he wrote me, “I think it was driven by her desire both to inoculate us with good manners and to establish or maintain social position amongst ‘the attractive people.’ Those urges must have been some mixture of insecurity, wanting to be admired by others, and a pre-digested sense of the proper order of the universe.”

The twining of dance and social advancement, of course, has a long history reaching back to the Renaissance, when dance manuals were full of tips about comportment and posture, as if to remind us that “illuminati” rhymes with “snotty.” Louis XIV’s great achievement in the history of ballet was in the 1660s to lead the idiom away from military arts like horse riding and fencing, where it had been couched, and to push it toward etiquette and decorum.

Because physical touch comes with an implicit set of guidelines and precautions, the successful deployment of same bespeaks sensitivity and self-restraint. As the motto of the dance academy where Ginger Rogers’s character works in Swing Time puts it, “To know how to dance is to know how to control oneself.” Or, as an etiquette guide popular in colonial America coached, “Put not thy hand in the presence of others to any part of thy body not ordinarily discovered.”

To this end, dancing, particularly ballroom and ballet, is often linked to the tropes of initiation and entrée—e.g., the first dance at weddings, or the first waltz at quinceañeras, wherein the father of the quinceañera dances with his daughter and then hands her off to her community. Once a dancer has been road-tested, she can be delivered to the new world she has chosen, thereupon to roar off into the night.

For professional dancers, the markers of social advancement are more aligned with quantities such as accreditation and celebrity. The flight path often runs: (1) Train till you bleed. (2) Join a company and distinguish yourself. (3) Write a memoir heavy on bonking. The prestige here is couched in steps 2 and 3, as the world marvels at what company you joined and what roles you danced. But there are lovely exceptions. In 1997 when the tap dancer Kaz Kumagai moved to New York from Sendai, Japan, at age nineteen, one of his early teachers, Derick K. Grant, was so impressed by Kumagai’s immersion into and respect for African-American culture—an understandably large part of the tap world—that Grant and other black dancers gave Kumagai the honorary “black” nickname Kenyon. Respect.

Regardless of whether you’re a social dancer or a professional one, all this weight can yield confusion and awkwardness. My ballroom classes took place in downtown Worcester, Massachusetts, in the basement of an imposing building that felt like the architectural equivalent of sclerosis. Once a week after school, twelve or so of us would gather and be indoctrinated in the rudimentary outlines of the fox-trot and the waltz. Chest up, shoulders down—how can you be upwardly mobile if you don’t have an erect spine?

I enjoyed spending time with my friends: two of the twelve were Carolyn and Dorothy, with whom I’d later do the Bus Stop. They lived in my neighborhood, and were among my closest friends. There was a lot of willed awkwardness about the dancing itself—if you made it look too easy or too fun, then you’d be curbing the amount of time you got to exploit the hallmarks of the adolescent experience, manufactured pain and squirming.

The lesson on offer didn’t seem to be about towing the line of being cool, or about dancing, but, rather, about interacting with members of the opposite sex. That a woman’s upper torso, save for her shoulders, was out of bounds was not news to me: I had two older sisters and thus knew that breasts and their environs were a no-go area. That sweaty hands were something to be avoided was a more novel idea to me, but certainly brushing my dewy palm against my hip before offering it to my dance partner was not difficult to master. I can wipe.

No, oddly, the biggest challenge of these lessons, it appeared to my then tender mind, had to do with table manners, or should I say, get-to-the-table manners. At these lessons, it turned out, dinner was served: a sturdy Crock-Pot full of gooey, fricasseed mystery awaited us at the end of each class. Each of us was to approach the food table, plop a big spoonful of rice and Crock-Potted goo onto our paper plate, and then tread very, very carefully the twenty or so feet to the dining table.

Not for us the sturdy reinforced cardboard that goes by the name Chinet. No, ours were the bendy, gossamer-thin paper plates which, if picked up by their edges, would immediately taco on you. Which same action caused a dribble of goop to cascade onto your bell-bottoms.

So my first true exposure to dance was, at heart, less kinesthetic than dry-cleanological.

* * *

Right around this same time in my life—this is the early 1970s—I’d had my first exposure to modern dance performed live. I was a second grader at the Bancroft School in Worcester, and at assembly one morning in the school’s auditorium, a woman danced for us. A zaftig, twenty-something gal in a tie-dyed leotard, she ambled out onto the stage and proceeded to thrash around to some percussive, conga-infused music, her body’s rolls of adipose tissue rippling and inadvertently bringing the neon blossoms of her bodysuit to life in the manner of a human lava lamp.

My schoolmates and I could not stop laughing. Why was she moving like that? I wondered. Why the tie-dyed leotard? At this point in my life, I’d become enamored of Carol Burnett and Lucille Ball, and I thought, Surely this pageant of flesh before my eyes is meant to be appreciated in the same light as Ms. Burnett and Ms. Ball’s work?

But, no. My homeroom teacher tapped me on the shoulder and looked at me crossly. Later that afternoon, our class was given a special admonitory lecture on art appreciation. We do not laugh at art, we were told. We admire it, we study it. We flat-line our gaping mouths and then cast over the remainder of our face a look of slightly dazed serenity. Later in our lives, we will resurrect this facial expression for run-ins with religious zealots, salespeople, art made from cat hair.

* * *

Whether you’re watching someone get jiggy with it, or you yourself are the jiggy-getter, you need to cultivate a sensitivity about the flesh on parade. This can be particularly acute for the jiggy-getters. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the most popular form of dancing, the minuet, took the idea that dance is a builder of character and ran with it. In having each couple dance alone with each other while all the other couples watched them, the minuet became a forum for judgment and tut-tutting that lacked only Dancing with the Stars–style score paddles: not only were the dancers currently in motion being silently judged on their technique, bearing, and posture, but, as Jack Anderson reminds us in Ballet & Modern Dance, their flaws in dancing were viewed as flaws in character, too. As Sarah, the duchess of Marlborough, said of one dancer who endured the gaze of the duchess’s gimlet eyes, “I think Sir S. Garth is the most honest and compassionate, but after the minuets which I have seen him dance . . . I can’t help thinking that he may sometimes be in the wrong.”

What’s interesting to me here is the grounds on which the dancer is being criticized: though the history of dance provides countless examples of people damning dance on the basis of wantonness and the ability of this particular branch of the arts to cause certain body parts to flap or rotate with an excessive vividness, the duchess and her criticism are decidedly bigger picture—she’s set her sights on honesty, compassion. We can almost see how, in the duchess’s eyes, Sir S. Garth is the type of dude who’ll step on a lot of toes, lie to the other dancers, and then ride home in his landau to not feed his kitten.

Other dancers, though, harness the moral gravitas they find in dance and use it to power a kind of sea change. Consider Jerome Robbins, who choreographed both for the ballet (Fancy Free, Afternoon of a Faun, Dances at a Gathering) and the theater (On the Town, Peter Pan, West Side Story). Robbins struggled for decades with his Judaism, at age thirteen chasing away schoolmates who peered into the Robbins family living room windows in Weehawken, New Jersey—they’d made faces while young Jerry Rabinowitz and a holy man from the local synagogue practiced reading the Torah. For the shame-filled young Robbins, ballet would have what he called a “civilizationizing” effect on his ancestral-tribal identity. “I affect a discipline over my body, and take on another language,” Robbins would write, “the language of court and Christianity—church and state—a completely artificial convention of movement—one that deforms and reforms the body and imposes a set of artificial conventions of beauty—a language not universal.”

* * *

One of the times that dance was a vehicle of entrée in my life, the idiom in question was neither ballroom nor ballet. In my junior year at the boarding school Hotchkiss, through the ministrations of a kindhearted high school pal, I was invited to the Gold and Silver Ball. Started in 1956, this New York City charity ball kicks off the winter breaks of teenage public and private schoolers in the Northeast, giving them an opportunity to swap stories about their parents’ divorce proceedings and to practice smuggling liquor into a non-stadium setting.

Back then the ball was held at the Plaza Hotel or the Waldorf Astoria, and featured the dulc...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 1501122258

- ISBN 13 9781501122255

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.8. Seller Inventory # 1501122258-2-1

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.8. Seller Inventory # 353-1501122258-new

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1501122258

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1501122258

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1501122258

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1501122258

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1501122258